Symbolism of Mordvin clothing

Clothing has always carried and still carries symbolic meaning. A symbol means an idea that the representatives of a community or culture regard as true or real. With symbols, their bearer is able to structure their world of emotions and to behave correctly, that is, in the way determined by their culture, as well as to communicate both of these to others. In this way, the representatives of a culture interpret and convey their world view and values to themselves, each other and future generations.

The first detailed descriptions of Mordvin clothing date back to the 1770s. The collections of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) contain two Mordvin tunics and an item of headgear. Around a hundred years later, Finnish ethnographer and archaeologist A. O. Heikel undertook a research trip to Mordvins with a view to studying Mordvin buildings and embroidery and collecting artefacts for the collections of the University of Helsinki. The trip took three years and produced an extensive collection of artefacts for people to see in Finland.

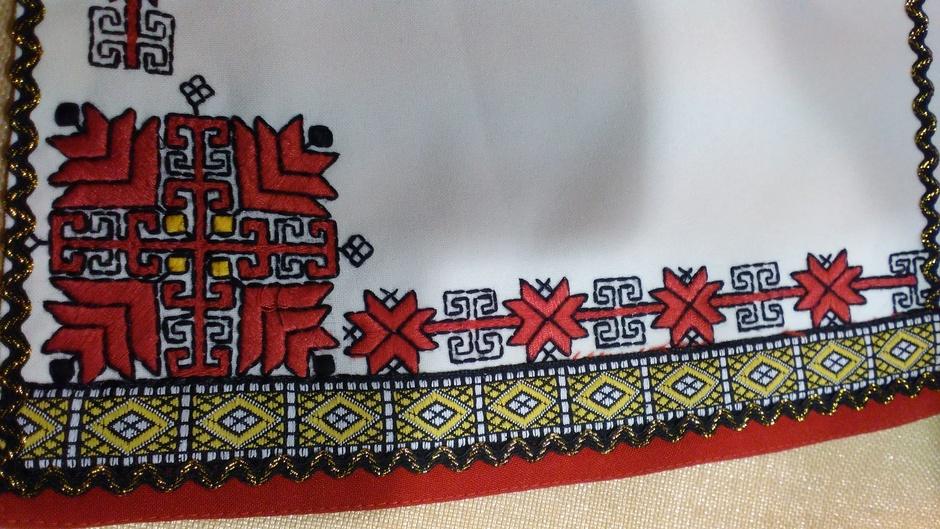

The main element of the Erzya and Moksha Mordvin female costume was a white tunic dress. It was sown from a piece of fabric folded in half, with the neckline cut in the middle and sleeves the width of the fabric added to the sides. The fabric was hemp or cotton. Embroidery and jewellery provided content to an otherwise simple costume, turning it into a means of communication.

Erzya Mordvins favoured a slender female body. Their tall and often conical headgear and figure-hugging, ankle-length tunic dresses accentuated this ideal of a woman. The effect was intensified by the vertical embroidered stripes of their dresses and the long hair braid and belt pendants. The most visible symbol of the Erzya woman’s identity is the back apron (pulogai, pulaks or pulokarks). By contrast, the Moksha Mordvin ideal was a stocky female body, which was achieved by wearing several dresses on top of each other and using a belt to shorten them. Headgear was low, square or turban-like in shape, and feet and legs were wrapped in several puttee cloths in different colours.

Simple tunic dresses were worn in everyday life, whereas in celebrations, a tunic with six embroidered stripes in the front and back was worn. The festive tunic of brides had four particularly wide embroidered stripes. It was only in girls’ autumn festivities that unmarried women wore fully and elaborately embroidered overdresses (pokaj).

The difference between girls and married women could be seen in their hairdos: Girls were bareheaded and combed their hair into braids. Erzya girls had a decorative tassel in their braid, while Moksha girls wore a headband. Married women, however, could not appear without headgear. The heavy, elaborately embroidered headgear was a symbol of the wife’s burdensome life, in contrast to the carefree life of an unmarried girl. Married women were not allowed to go around barefooted, either. Instead, their feet and legs were wrapped in several cloths: thick legs were an indicator of a strong worker as well as of feminine beauty.

Embroidery not only served decorative purposes but also served as a guard of sorts against evil. Jewellery protected against the evil eye (a look or stare resulting in bad luck or harm) and warded off ill health. It was believed that a pig’s tooth hanging in the hair braid decoration made you sleep well, a cock’s bone in your necklace protected against the common cold, and nuts and cowrie shells boosted fertility. The nature of protection provided by embroidery was comprehensive: the neckline, seams and hems of the tunic dress were stitched full of star and cross designs as well as designs with animal motifs such as “duckfeet”, “wings” and “hare’s feet”.

Embroidery reflected the woman’s handicraft skills, her mental and spiritual capital and her working capacity. The number of pieces of embroidered clothing could be a sign of wealth. Elaborate headgear, jewellery and coin and pearl decorations belonged exclusively to women and were passed on to their daughters. Although women were otherwise in a position subordinate to men, their clothing and jewellery were their personal property to which their husband or his relatives had no right.

Not only the wealth but also the family emblem was displayed in women’s clothing. Some embroidery patterns resemble family and ownership symbols that were attached to property, livestock and tools or carved on trees to mark hunting tracks, for example. Such ownership symbols were found particularly in the headgear and fringed back aprons of married women.

There was also variation in Erzya and Moksha clothing from one locality to another. Headgear shapes, Erzyan back aprons, jewellery types, embroidery techniques and colour schemes were details that revealed where the wearer was from.

Mordvin women’s costumes formed a complex whole. They reflected the women’s subordinate role in the Mordvin community, with the newlywed wife being totally at the mercy of her husband and his relatives. High expectations were put on a young woman by the community, and she had to be able to meet these expectations. She wore clothes in which each needle stitch protected their bearer and communicated her internal values and working capacity. When engaged to be married, a girl had to make a great effort in making her trousseau (set of clothes and household linen the bride brings with her when she gets married), and she had to earn the community’s approval by means of her skills and the number of her embroidered items. Mental and spiritual capital was also required when getting married: by performing bridal laments, the bride says goodbye to her previous life and seeks access to her new life. This role was prepared for since childhood. Making embroidery was not just pastime handicrafts. It was also a survival strategy, both an internal obligation as well as an external one enforced by the community.

Rich in colours and jewellery, Erzya and Moksha clothing did not attract the attention of expeditioners without reason. The control performed by the community ensured the preservation of their clothing practically unchanged for centuries. In places, the process of change did not accelerate until as late as the 1930s, when it became possible to buy multicoloured fabrics and abandon clothing that required a great deal of effort to make. The change was accelerated by the compulsory measures taken to implement the cultural revolution of the Soviet Union. Moksha women did not give up their folk costumes entirely. Instead, they adapted them in accordance with the new era and new requirements. In places, the embroidered tunic dress retained its multifaceted status: it was supplemented by new colourful clothing items that made the costume easy to care for while at the same time preserving the people’s look.

Embroidery is no longer the virtue of every woman, and the message of embroidery patterns cannot be read like an open book. Today, embroidery is a symbol of the national identity of Mordvins, a kind of national costume people wear on special occasions such as weddings or performances. There are fewer and fewer of those who can still read the code language embedded in the costumes.

Sources

Sukukansapäivien satoa. Kirjoituksia ja puheenvuoroja suomalais-ugrilaisuudesta [Proceedings of the Finno-Ugric Days: Articles and Lectures on Finno-Ugric Peoples]. Castrenianumin toimitteita 57, Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. Ed. Marja Lappalainen. Helsinki 2002.

Ildikó Lehtinen. Valkoinen koivumetsä – mordvalaisten pukujen symboliikkaa [White Birch Wood – symbolism of Mordvin clothing] pp. 135–150.

A. O. Heikel: Mordvalaisten pukuja ja kuoseja. Trachten und Muster der Mordvinen [Mordvin Clothing and Patterns]. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Kansatieteellisiä julkaisuja 1 [Ethnographic publications de la Société Finno-Ougrienne – Publications of the Finno-Ugrian Society]. Helsinki 1899.